CPU: 61% lower pipeline cost. The real bottleneck was never compute.

How execution-level data unlocked 61% more science per dollar without changing hardware accelerators

const metadata = ;

Introduction

When cloud pipelines run slowly, the default response is often to reach for accelerators: larger instances, more cores, or GPUs. In this study, we explored a different approach.

Before introducing hardware acceleration, we asked a simpler question: Are we actually using the CPUs we already pay for?

We worked with Superfluid Dx's production cf-mRNA RNA-seq pipeline and used execution-level observability to understand where time and cost were being lost. The result was counterintuitive: most of the latency and cost issues could be addressed without changing the compute model.

By fixing I/O bottlenecks, instance selection, and configuration mismatches, we reduced pipeline turnaround time by ~33% and improved cost efficiency by up to 61% per dollar spent, using CPUs alone.

Scientific context

Superfluid is developing the first high-performance, predictive blood-based test for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and related dementias that directly assays mRNA transcripts from the brain via its platform technology of cell-free messenger RNA (cf-mRNA) analysis and machine learning. This next-generation liquid biopsy technology enables non-invasive measurement of the dynamic biology of organs throughout the body, including the brain. A precise understanding of the underlying pathways of disease has the potential to transform AD care and treatment.

Superfluid is led by a small, highly accomplished team, including founder Steve Quake (Stanford Professor and Head of Science at CZI) and CEO Gajus Worthington (former founder and CEO of Fluidigm). The company has published extensively in peer-reviewed journals and is funded by notable investors, including Brook Byers and Reid Hoffman. Superfluid is also supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation.

The baseline problem: Expensive instances, idle CPUs

The initial pipeline configuration requested up to 480GB of RAM, with observed peaks above 1TB during STAR alignment. AWS Batch responded by provisioning oversized instances to satisfy these memory requirements.

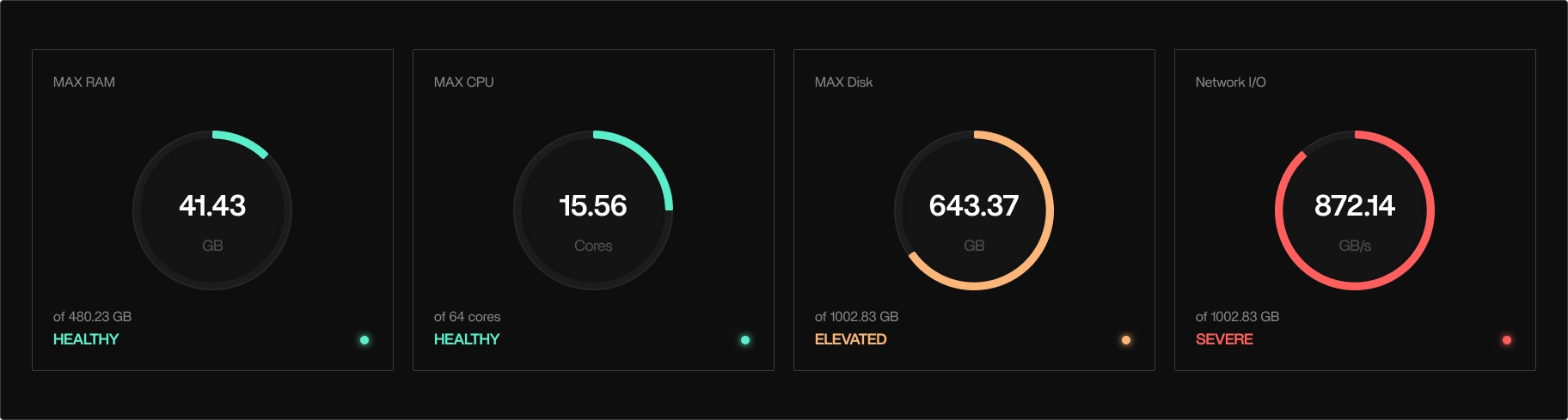

Execution-level data told a different story:

- CPU utilization peaked at ~15–18 cores on 64-core instances

- Average CPU utilization stayed below 25%

- Disk I/O and network throughput were consistently saturated

- STAR frequently stalled while waiting on data rather than compute

Tracer showed an I/O bound system. (Screenshot from Tracer)

On paper, the pipeline looked compute-heavy. In production, it behaved like an I/O-bound system.

This distinction matters. Scaling CPUs does not help when CPUs are idle.

Why configuration tuning alone wasn't enough

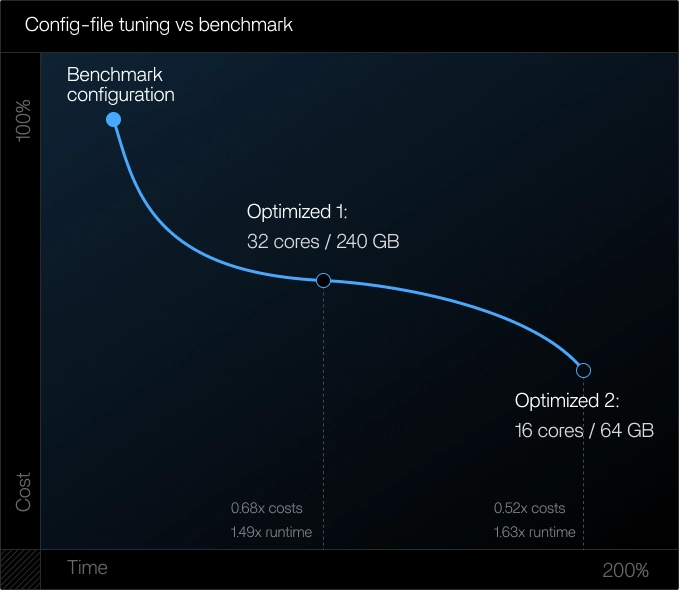

The first optimization attempt focused on configuration-level changes:

- Reduced requested cores

- Lowered memory limits

- Allowed AWS Batch to select instances dynamically

The results were mixed:

- Cost dropped by up to ~50%

- Runtime often increased by 1.5×–1.6×

- Increased instance churn added startup and scheduling overhead

Without controlling the underlying instance architecture, configuration tuning alone traded cost for time, or time for cost, but rarely improved both simultaneously.

Instance architecture mattered more than instance size

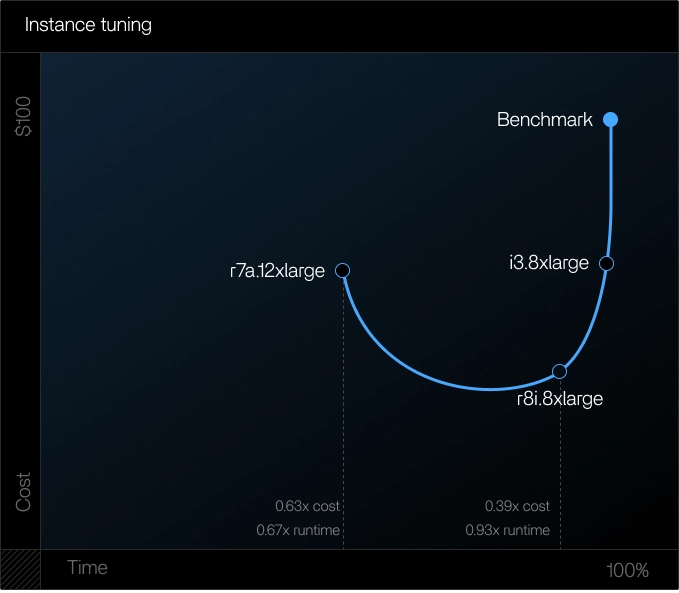

The largest gains came from explicitly selecting the right CPU instance families.

Key observations:

- Older instance families (e.g., m4) increased runtime by up to 60%

- Newer, memory-optimized instances consistently outperformed previous generations

- I/O-heavy and memory-intensive tools (STAR, Picard, GATK) benefited disproportionately

Two configurations stood out:

r7a.12xlarge

- ~33% faster runtime

- ~37% lower cost

r8i.8xlarge

- ~61% lower cost

- Near-baseline runtime

Both matched the pipeline's true constraints: memory bandwidth, I/O throughput, and modern CPU architecture.

The real bottleneck: Disk and network I/O

Execution-level metrics showed:

- Disk usage peaking above 600 GB

- Network throughput consistently saturated

- CPU and RAM operating within healthy ranges

Further investigation confirmed that data movement, not computation, dominated runtime.

Supporting benchmarks showed:

- NVMe-backed instances delivered 2–3× higher read throughput

- S3-to-local-disk transfer speed varied dramatically by region and instance type

- Network performance, not local compute, set the upper bound on throughput

This explains why larger instances did not help, and why newer, I/O-optimized instances did.

Smaller optimizations that compounded

Once the primary bottlenecks were addressed, several smaller changes compounded into meaningful gains.

Spot instances

- Up to ~67% lower cost at comparable runtime

- Required interruption-safe pipeline configuration

Region selection

- On-demand pricing was cheaper in us-east-1

- Better availability of memory-optimized instances

- Faster read-heavy operations due to infrastructure differences

Feature availability

- Not all instance families are available in all regions

- Region choice constrained viable architectures

These optimizations were situational, but when applicable, they delivered outsized returns.

The outcome: more science per hour, more science per dollar

After applying these changes:

- End-to-end runtime dropped from 3+ hours to ~2 hours

- Cost per pipeline decreased by 36%–60%, depending on configuration

- Each compute hour produced ~33% more usable output

- Cost efficiency improved by ~61% per dollar spent

Critically, this was achieved without changing the scientific workflow and before introducing GPUs.

Lessons learned

Idle CPUs are a signal, not a success

Low CPU utilization usually indicates I/O or scheduling bottlenecks, not over-provisioning.

Instance family matters more than instance size

Modern architectures with better memory and I/O characteristics consistently outperformed larger but older instances.

Configuration tuning without architectural control is incomplete

Letting the scheduler choose instances obscures important performance tradeoffs.

I/O dominates at scale

For data-heavy pipelines, disk and network throughput define performance ceilings long before CPU limits are reached.

Cost efficiency compounds

Small improvements—region choice, spot usage, NVMe—stack once the primary bottleneck is removed.

Why this matters before GPUs

A common conclusion after slow pipelines is that CPUs are insufficient. This work shows that assumption is often premature.

When teams understand execution behavior, they can:

- Avoid unnecessary hardware upgrades

- Establish a fair baseline for acceleration

- Ensure GPUs, when introduced, solve the right problem

Before accelerating pipelines, it is worth asking whether existing resources are being used effectively.

In this case, execution-level visibility showed that the biggest gains came not from more compute, but from better alignment between workload behavior and infrastructure design.

Only after achieving that alignment did it make sense to explore hardware acceleration.

We used this CPU-focused optimization as the foundation for the GPU acceleration work that followed. Read: [Breaking the STAR bottleneck with NVIDIA Parabricks](/blog/nvidia-parabricks-star-alzheimers-rnaseq).

Get started with Tracer

Tracer is a kernel-level observability solution that goes beyond metadata and heuristics. Their compute intelligence logs system workloads and captures ground-truth signals that applications can't. When workflows fail, application-layer visibility collapses. Tracer rebuilds the full execution path of any pipeline run, every invocation, every stall, every failure. It sees it all and shows you how to fix it.

Tracer is open source and because it runs close to the metal it requires zero code changes or rearchitecturing to work. It installs in one command line and because it's built using eBPF it's secure and has close to zero overhead.